Harry Langdon's Poverty Row Curtain Call

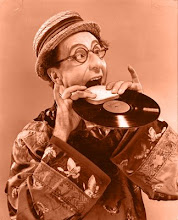

By 1940, the glory days for Harry Langdon were long past. Once considered a serious rival to Chaplin, Langdon had spent the last decade bouncing around Hollywood, picking up steady, if mostly low-profile, employment. His first work in sound, a series of shorts for Hal Roach, should have been the stepping stone towards resuming work in features. Instead, their poor reception, coupled with his growing reputation as a difficult actor, seemed to eliminate any possibility of further work as a star attraction in feature films. While he did secure the occasional plum role in features, such as his wonderful Communist sanitation worker in Al Jolson's Hallelujah, I'm a Bum! (1933), he spent most of the years before his death in 1944 as a star of modest shorts at RKO, Paramount, Educational, and Columbia. Perhaps more fortuitous was his work as a gag man and scenarist for his friend Stan Laurel. His name appears in the credits for the Laurel and Hardy features Block-Heads (1938), The Flying Deuces (1939), A Chump at Oxford (1940), and Saps at Sea (1940), and film historian Glenn Mitchell has suggested that Laurel's hiring of Langdon may in part have been repayment for his perceived "debt" to Langdon's similar screen persona. It's also to be assumed that when Langdon appeared opposite Babe Hardy in Zenobia (1939) during Laurel's extended absence from Roach, it was with Laurel's tacit approval. On all of the aforementioned Laurel and Hardy films, Langdon shares script and/or story credit with Charley Rogers, one of Stan Laurel's closest friends and former director of the bulk of Langdon's failed series for Roach. Rogers, born in Birmingham, England in 1887, was a former music hall comedian and, aside from directing and writing at the Roach studios, had been appearing in bit roles there from 1928 on, his gaunt figure and stern and hawkish features making him ripe for such mock-dignified roles as butlers, parsons, and prime ministers. This was far from his first work as a film actor, however. Rogers' screen career began rather auspiciously with his role as the Artful Dodger in the earliest known American feature film, Oliver Twist, in 1912. But more about the dour Charley Rogers in a moment.

By 1940, the glory days for Harry Langdon were long past. Once considered a serious rival to Chaplin, Langdon had spent the last decade bouncing around Hollywood, picking up steady, if mostly low-profile, employment. His first work in sound, a series of shorts for Hal Roach, should have been the stepping stone towards resuming work in features. Instead, their poor reception, coupled with his growing reputation as a difficult actor, seemed to eliminate any possibility of further work as a star attraction in feature films. While he did secure the occasional plum role in features, such as his wonderful Communist sanitation worker in Al Jolson's Hallelujah, I'm a Bum! (1933), he spent most of the years before his death in 1944 as a star of modest shorts at RKO, Paramount, Educational, and Columbia. Perhaps more fortuitous was his work as a gag man and scenarist for his friend Stan Laurel. His name appears in the credits for the Laurel and Hardy features Block-Heads (1938), The Flying Deuces (1939), A Chump at Oxford (1940), and Saps at Sea (1940), and film historian Glenn Mitchell has suggested that Laurel's hiring of Langdon may in part have been repayment for his perceived "debt" to Langdon's similar screen persona. It's also to be assumed that when Langdon appeared opposite Babe Hardy in Zenobia (1939) during Laurel's extended absence from Roach, it was with Laurel's tacit approval. On all of the aforementioned Laurel and Hardy films, Langdon shares script and/or story credit with Charley Rogers, one of Stan Laurel's closest friends and former director of the bulk of Langdon's failed series for Roach. Rogers, born in Birmingham, England in 1887, was a former music hall comedian and, aside from directing and writing at the Roach studios, had been appearing in bit roles there from 1928 on, his gaunt figure and stern and hawkish features making him ripe for such mock-dignified roles as butlers, parsons, and prime ministers. This was far from his first work as a film actor, however. Rogers' screen career began rather auspiciously with his role as the Artful Dodger in the earliest known American feature film, Oliver Twist, in 1912. But more about the dour Charley Rogers in a moment.In 1940, Harry Langdon was given his first starring role in a feature since Heart

Trouble in 1928. Granted, it wasn't for one of the Big Four studios in Hollywood; in fact, it was for Producers Releasing Corporation, a studio that rested, arguably, at the bottom of the Poverty Row barrel, but it was a genuine opportunity for Langdon, nonetheless. One wonders how Langdon ended up at PRC in the first place. Did he approach PRC or vice-versa? I suspect the latter as Misbehaving Husbands bears no resemblance in form or tone to any other Harry Langdon feature and feels as if it may have been written with someone else, or maybe no one, in mind. Misbehaving Husbands is a comedy of errors and variations on its razor-thin plot would fuel the first decade of mediocre TV sitcoms. Harry appears as Henry Butler, absent-minded manager of a successful department store. Henry is so wrapped up in his work that he forgets his wedding anniversary and misses the surprise party his wife Effie (Betty Blythe) is throwing that night. Two of the partygoers just happen to be passing by Henry's department store when Henry just happens to be working with one of the store's models just behind a backlit shade in a display window. The gossipy partygoers immediately head to the party where they spread hushed innuendo about Henry's whereabouts. Meanwhile, Henry has accidentally broken one of the store's female mannequins, nicknamed "Carol". After taking it to a waxworks to get it repaired, he's detained by the police who want to know what he's done with the "body" that bystanders saw in the back of his car. According to the rules of cheap comedy, Henry is forced to refer to the mannequin as "she" and "Carol" and never as "the mannequin" which results in his interrogation lasting hours. By the time he's done, the party is over and Effie has been nearly convinced by her newly-divorced friend Grace (Esther Muir) that Henry is a philandering filthbag. When Henry returns home with the mannequin's high-heeled shoe and garter, Effie decides to take Grace's advice and get a divorce. But Grace's divorce lawyer, Gilbert Wayne (Gayne Whitmer), is a conman who plants false evidence to make sure the couple splits. As neither Henry or Effie will relinquish the house, Effie's niece (Luana Walters) and law student Bob Grant (Ralph Byrd at his Dick Tracyest) are appointed live-in witnesses to testify that the couple are separated . Together they foil the lawyer's scheme, get Henry and Effie back together, and, as is required by B movie law, fall in love. The script by Vernon Smith and Claire Parrish is from hunger and there are almost no laugh lines in the film's 58 minute running time. Given that the script provides so little for the actors to work with, in the hands of another actor, the role of Henry Butler could have been quite colorless. But as Langdon's special appeal as a comedian lay in his unique performance style rather than any particular verbal "turn", Langdon is easily capable of making the role his own. Henry Butler as performed by Langdon, is a kind of demystified version of his silent "baby" character, now grown, believably married, and with real world responsibilities, but still innocently endearing. His intelligence is never questioned; in fact, his glasses give him a bookish appearance. He's mild-mannered but capable of successfully managing his department store through his own fussy doggedness, and that he would also have a (mostly) successful marriage is reasonable due to those same traits (Betty Blythe plays Effie as similarly mild if more levelheaded). He's still a comic innocent, though, and many of the plot complications are due to his innate naivete. The gestural trademarks of his silent films are also intact, especially the hand placed pensively to the mouth in worry and the jerky, unsure movements. Harry's stuttering speech nicely reflects his semiconscious, barely controlled body l

Trouble in 1928. Granted, it wasn't for one of the Big Four studios in Hollywood; in fact, it was for Producers Releasing Corporation, a studio that rested, arguably, at the bottom of the Poverty Row barrel, but it was a genuine opportunity for Langdon, nonetheless. One wonders how Langdon ended up at PRC in the first place. Did he approach PRC or vice-versa? I suspect the latter as Misbehaving Husbands bears no resemblance in form or tone to any other Harry Langdon feature and feels as if it may have been written with someone else, or maybe no one, in mind. Misbehaving Husbands is a comedy of errors and variations on its razor-thin plot would fuel the first decade of mediocre TV sitcoms. Harry appears as Henry Butler, absent-minded manager of a successful department store. Henry is so wrapped up in his work that he forgets his wedding anniversary and misses the surprise party his wife Effie (Betty Blythe) is throwing that night. Two of the partygoers just happen to be passing by Henry's department store when Henry just happens to be working with one of the store's models just behind a backlit shade in a display window. The gossipy partygoers immediately head to the party where they spread hushed innuendo about Henry's whereabouts. Meanwhile, Henry has accidentally broken one of the store's female mannequins, nicknamed "Carol". After taking it to a waxworks to get it repaired, he's detained by the police who want to know what he's done with the "body" that bystanders saw in the back of his car. According to the rules of cheap comedy, Henry is forced to refer to the mannequin as "she" and "Carol" and never as "the mannequin" which results in his interrogation lasting hours. By the time he's done, the party is over and Effie has been nearly convinced by her newly-divorced friend Grace (Esther Muir) that Henry is a philandering filthbag. When Henry returns home with the mannequin's high-heeled shoe and garter, Effie decides to take Grace's advice and get a divorce. But Grace's divorce lawyer, Gilbert Wayne (Gayne Whitmer), is a conman who plants false evidence to make sure the couple splits. As neither Henry or Effie will relinquish the house, Effie's niece (Luana Walters) and law student Bob Grant (Ralph Byrd at his Dick Tracyest) are appointed live-in witnesses to testify that the couple are separated . Together they foil the lawyer's scheme, get Henry and Effie back together, and, as is required by B movie law, fall in love. The script by Vernon Smith and Claire Parrish is from hunger and there are almost no laugh lines in the film's 58 minute running time. Given that the script provides so little for the actors to work with, in the hands of another actor, the role of Henry Butler could have been quite colorless. But as Langdon's special appeal as a comedian lay in his unique performance style rather than any particular verbal "turn", Langdon is easily capable of making the role his own. Henry Butler as performed by Langdon, is a kind of demystified version of his silent "baby" character, now grown, believably married, and with real world responsibilities, but still innocently endearing. His intelligence is never questioned; in fact, his glasses give him a bookish appearance. He's mild-mannered but capable of successfully managing his department store through his own fussy doggedness, and that he would also have a (mostly) successful marriage is reasonable due to those same traits (Betty Blythe plays Effie as similarly mild if more levelheaded). He's still a comic innocent, though, and many of the plot complications are due to his innate naivete. The gestural trademarks of his silent films are also intact, especially the hand placed pensively to the mouth in worry and the jerky, unsure movements. Harry's stuttering speech nicely reflects his semiconscious, barely controlled body l anguage, but is much more toned down here than in his shorts in which he's often hilariously unintelligible. If anything, Harry's "adult" character bears a close resemblance to that of Victor Moore, if much more eccentric. In one of Misbehaving Husbands' better moments, Harry angrily asserts himself to Effie's lawyer after he suggests Harry keep quiet. Harry winds into motion, accenting his speech with exaggerated and deliberate gestures, as if mimicking someone else's half-remembered tirade, doing his best to make sure people understand that he's angry. "I can't open my mouth in my own home?? Well, let me tell you something! I'm a free American citizen! I pay taxes! And I have a right to free speech! And liberty! And, uh, pursuit of happiness n' all that stuff!!" Flying off the handle, he storms around the room, pounding the furniture. "I paid for this! AND THAT! AND THAT!!" But in the process, Harry accidentally topples a small figurine from a table. The moment it hits the floor, his rage is gone. He quickly sits down, hands in his lap, fearing the consequences. Look.. I know this doesn't sound funny. Whatever subtle and mysterious personal tics make Langdon's comedy effective are notoriously hard to describe in text. I refuse to accept responsibility.

anguage, but is much more toned down here than in his shorts in which he's often hilariously unintelligible. If anything, Harry's "adult" character bears a close resemblance to that of Victor Moore, if much more eccentric. In one of Misbehaving Husbands' better moments, Harry angrily asserts himself to Effie's lawyer after he suggests Harry keep quiet. Harry winds into motion, accenting his speech with exaggerated and deliberate gestures, as if mimicking someone else's half-remembered tirade, doing his best to make sure people understand that he's angry. "I can't open my mouth in my own home?? Well, let me tell you something! I'm a free American citizen! I pay taxes! And I have a right to free speech! And liberty! And, uh, pursuit of happiness n' all that stuff!!" Flying off the handle, he storms around the room, pounding the furniture. "I paid for this! AND THAT! AND THAT!!" But in the process, Harry accidentally topples a small figurine from a table. The moment it hits the floor, his rage is gone. He quickly sits down, hands in his lap, fearing the consequences. Look.. I know this doesn't sound funny. Whatever subtle and mysterious personal tics make Langdon's comedy effective are notoriously hard to describe in text. I refuse to accept responsibility.The billing for Misbehaving Husbands is peculiar. Unquestionably the star, Langdon gets first billing in the film itself (although not above the title), but he takes third billing behind Ralph Byrd and Esther Muir on the poster and in promotional materials. While Byrd was a draw in 1940, Muir was most certainly not. In England, where the film was well received, Misbehaving Husbands was not only promoted as a full-blown Harry Langdon comedy, but also as his first talking picture!

"Who is telling this story, anyway?" "He is.."

The following year found Harry Langdon at a little further

up Poverty Row at Monogram, home of Johnny Mack Brown and the East Side Kids. This time around, the film was tailor-made for Langdon, and although Double Trouble bills Harry alone above the title, he actually appears as one half of a team with his old friend Charley Rogers. How this came about is a mystery, but it's certainly not impossible that Rogers and Langdon's mutual friend Stan Laurel made the suggestion that they give it a go. As Laurel and Hardy gagmen, perhaps they acted out the routines in gag sessions and someone felt they were good enough at it to make a buck or two. Laurel and Hardy certainly seem to have been the inspiration. Although unique enough in his own sour and reproachful way, Rogers can be seen as a fast-talking, skinny, and British Babe Hardy. Langdon comes full circle in his role in the partnership as pseudo-Stan. Harry Langdon, of course, is still Harry Langdon, more now than ever. He wears a close approximation of his silent costume, and even though he is now almost sixty-two, in several scenes he almost looks as eerily young as he did in 1927. The only nod to his new role as Rogers' comedy partner is a mock-British accent, mercifully dropped and forgotten after a few early scenes. In Double Trouble, Rogers and Langdon are brothers Bert and Alf Prattle, refugees from the London blitz. They've been adopted by blustery California bean tycoon John Whitmore (Frank Jaquet) and his wife (Mira McKinney) who were mislead to believe Bert and Alf were children. They even have a nursery all set up for them. It's a humorous misunderstanding rife with comic potential! Meanwhile, Whitmore's daughter Peggy (Catherine Lewis) has fallen for her father's key advertising man, the wisecracking Sparky Marshall (Dave O'Brien, best remembered as reporter Johnny Layton from The Devil Bat with Bela Lugosi), and unless Sparky can win her father's respect, there will be no wedding. Sparky comes up with a scheme to have the bean company sponsor a extremely valuable necklace, cleverly taking advantage of the association between beans and valuable jewelry. Rogers and Langdon have been given jobs in the Whitmore cannery and, by some convoluted contrivance, Harry ends up putting the necklace in an empty bean can as a surprise for a pretty coworker he has been flirting with (clip here). The can accidentally ends up getting sealed and sent to market. With only Harry's handwritten note to the coworker on the top of the can to identify it, a nationwide treasure hunt ensues. Bean sales skyrocket. But Rogers and Langdon must find the can before a consumer does. By another contrivance, they manage to track it down to a waterfront cafe and, by dressing as unconvincing women, retrieve it. All ends happily. Rogers and Langdon display an obvious camaraderie, but although their moments as a team show a clear debt to Laurel and Hardy, their partnership takes a backseat to Langdon's solo turns. This is not exactly a bad thing. Rogers and Langdon introduce themselves to Mrs. Whitmore with a cute if extremely strange speech, punctuated by Harry's hiccuping, ab

up Poverty Row at Monogram, home of Johnny Mack Brown and the East Side Kids. This time around, the film was tailor-made for Langdon, and although Double Trouble bills Harry alone above the title, he actually appears as one half of a team with his old friend Charley Rogers. How this came about is a mystery, but it's certainly not impossible that Rogers and Langdon's mutual friend Stan Laurel made the suggestion that they give it a go. As Laurel and Hardy gagmen, perhaps they acted out the routines in gag sessions and someone felt they were good enough at it to make a buck or two. Laurel and Hardy certainly seem to have been the inspiration. Although unique enough in his own sour and reproachful way, Rogers can be seen as a fast-talking, skinny, and British Babe Hardy. Langdon comes full circle in his role in the partnership as pseudo-Stan. Harry Langdon, of course, is still Harry Langdon, more now than ever. He wears a close approximation of his silent costume, and even though he is now almost sixty-two, in several scenes he almost looks as eerily young as he did in 1927. The only nod to his new role as Rogers' comedy partner is a mock-British accent, mercifully dropped and forgotten after a few early scenes. In Double Trouble, Rogers and Langdon are brothers Bert and Alf Prattle, refugees from the London blitz. They've been adopted by blustery California bean tycoon John Whitmore (Frank Jaquet) and his wife (Mira McKinney) who were mislead to believe Bert and Alf were children. They even have a nursery all set up for them. It's a humorous misunderstanding rife with comic potential! Meanwhile, Whitmore's daughter Peggy (Catherine Lewis) has fallen for her father's key advertising man, the wisecracking Sparky Marshall (Dave O'Brien, best remembered as reporter Johnny Layton from The Devil Bat with Bela Lugosi), and unless Sparky can win her father's respect, there will be no wedding. Sparky comes up with a scheme to have the bean company sponsor a extremely valuable necklace, cleverly taking advantage of the association between beans and valuable jewelry. Rogers and Langdon have been given jobs in the Whitmore cannery and, by some convoluted contrivance, Harry ends up putting the necklace in an empty bean can as a surprise for a pretty coworker he has been flirting with (clip here). The can accidentally ends up getting sealed and sent to market. With only Harry's handwritten note to the coworker on the top of the can to identify it, a nationwide treasure hunt ensues. Bean sales skyrocket. But Rogers and Langdon must find the can before a consumer does. By another contrivance, they manage to track it down to a waterfront cafe and, by dressing as unconvincing women, retrieve it. All ends happily. Rogers and Langdon display an obvious camaraderie, but although their moments as a team show a clear debt to Laurel and Hardy, their partnership takes a backseat to Langdon's solo turns. This is not exactly a bad thing. Rogers and Langdon introduce themselves to Mrs. Whitmore with a cute if extremely strange speech, punctuated by Harry's hiccuping, ab out how they survived after the ship they were traveling on was torpedoed. As an introductory setpiece, it's their least Laurel and Hardy-ish, but it's not particularly funny, either. In a somewhat better moment as a team, Harry and Charley are sleeping on the floor of their nursery (after having demolished their cribs) when a gust of wind sweeps an inflatable pool toy into the room. For reasons beyond human understanding, the pool toy hovers menacingly in the air over the two men for ages. Harry is the first to notice, and his abstract logic sounds suspiciously Laurel-like.

out how they survived after the ship they were traveling on was torpedoed. As an introductory setpiece, it's their least Laurel and Hardy-ish, but it's not particularly funny, either. In a somewhat better moment as a team, Harry and Charley are sleeping on the floor of their nursery (after having demolished their cribs) when a gust of wind sweeps an inflatable pool toy into the room. For reasons beyond human understanding, the pool toy hovers menacingly in the air over the two men for ages. Harry is the first to notice, and his abstract logic sounds suspiciously Laurel-like.Harry: Hey, Alf.. Sorry to disturb you, but did you ever have a nightmare?

Charley: Yes. I had one in London before we left.

Harry: Did it like you?

Charley: Did it like me? How do I know?

Harry: Well, its followed you over here. Look up and see if you recognize it as the same one.

At the brothers flee, the now clearly lighter-than-air (and possibly possessed) toy becomes attached to Harry's nightshirt. Hilarity ensues. While hardly approaching the quality of Langdon's silent work, Double Trouble has a lot of charm, exemplified by the Music Hall-themed opening credit sequence in which you can hear the orchestra warming up before kicking into the overture. And thanks to Monogram's legendary laxity, it also features Harry flipping the bird. Can't beat that!

Although it does have its moments, charm is something seriously lacking from the second and final Rogers and Langdon film, House Of Errors, produced the same year at PRC. The story is credited to Harry Langdon but, aside from a few unique touches, it could have been the work of any PRC scenarist. Charley and Harry are again Bert and Alf, now working as newspaper deliverymen who dream of becoming full-fledged reporters. Overhearing a conversation between the editor and a reporter about a miraculous new machine gun being developed by a local inventor, Bert and Alf head out to get the scoop. They plant themselves in the inventor's house as a valet and butler and soon find themselves competing for the story with another reporter, the smoothtalking lowlife Jerry Fitzgerald (played by the unbelievably obnoxious Ray Walker). Jerry has his eye on the inventor's daughter Florence (Marian Marsh) who happens to be engaged to a lowlife cad who wants to sell the gun to the Axis forces, etc.. Rogers and Langdon are much less of a team this time around. Harry has a lot of fairly funny solo turns, but Rogers' character has been streamlined into a standard disapproving straightman with dialogue consisting primarily of variations on "What are you doing now??". Among the better comic set-ups is an extended, and completely peripheral, scene in a flophouse. Harry can't get comfortable unless a large picture hanging on the wall behind the beds is properly straighten

Although it does have its moments, charm is something seriously lacking from the second and final Rogers and Langdon film, House Of Errors, produced the same year at PRC. The story is credited to Harry Langdon but, aside from a few unique touches, it could have been the work of any PRC scenarist. Charley and Harry are again Bert and Alf, now working as newspaper deliverymen who dream of becoming full-fledged reporters. Overhearing a conversation between the editor and a reporter about a miraculous new machine gun being developed by a local inventor, Bert and Alf head out to get the scoop. They plant themselves in the inventor's house as a valet and butler and soon find themselves competing for the story with another reporter, the smoothtalking lowlife Jerry Fitzgerald (played by the unbelievably obnoxious Ray Walker). Jerry has his eye on the inventor's daughter Florence (Marian Marsh) who happens to be engaged to a lowlife cad who wants to sell the gun to the Axis forces, etc.. Rogers and Langdon are much less of a team this time around. Harry has a lot of fairly funny solo turns, but Rogers' character has been streamlined into a standard disapproving straightman with dialogue consisting primarily of variations on "What are you doing now??". Among the better comic set-ups is an extended, and completely peripheral, scene in a flophouse. Harry can't get comfortable unless a large picture hanging on the wall behind the beds is properly straighten ed. He walks precariously along the molding on the wall, trying to align the picture while simultaneously trying not to fall off onto the occupants of the beds below. Monte Collins, another Columbia shorts veteran, also appears in this sequence as the requisite Owner-of-a-Flea-Circus-in-a-Flophouse who loses his "performers". While the plot Langdon concocted for House of Errors is perfunctory at best, the film's bizarre ending does reflect his taste for the macabre. Florence and her fiance, the Villainous Cad, are eloping in a biplane (she was in no way coerced and has shown little indication that she likes Jerry). Harry accidentally shoots it out of the sky with the machine gun, sending it crashing through the roof of the inventor's house. Inside, irritating Jerry rescues Florence from the wreckage of the plane and they embrace.. and behind them you can see the lifeless body of the villain hanging from the second cockpit! An explosion causes Florence to faint into Harry's lap where he "grabs" kisses from her lips and "eats" them.

ed. He walks precariously along the molding on the wall, trying to align the picture while simultaneously trying not to fall off onto the occupants of the beds below. Monte Collins, another Columbia shorts veteran, also appears in this sequence as the requisite Owner-of-a-Flea-Circus-in-a-Flophouse who loses his "performers". While the plot Langdon concocted for House of Errors is perfunctory at best, the film's bizarre ending does reflect his taste for the macabre. Florence and her fiance, the Villainous Cad, are eloping in a biplane (she was in no way coerced and has shown little indication that she likes Jerry). Harry accidentally shoots it out of the sky with the machine gun, sending it crashing through the roof of the inventor's house. Inside, irritating Jerry rescues Florence from the wreckage of the plane and they embrace.. and behind them you can see the lifeless body of the villain hanging from the second cockpit! An explosion causes Florence to faint into Harry's lap where he "grabs" kisses from her lips and "eats" them.While this was the last feature Langdon starred in, it wasn't his final appearance in features. He turned up in supporting character roles in three more features for Monogram, Spotlight Scandals (1943), Hot Rhythm and Block Busters (both 1944), and his last, Swingin' On a Rainbow (1945, released after his death), for Republic. The decision to withdraw from starring roles in features likely rested with Langdon and not PRC or Monogram. Harry Langdon was still a audience draw in the early 40s, if a minor one, and his three B features could not have lost money for either studio, considering their shoestring budgets. As Langdon's continuing work for PRC and Monogram testifies, he was more than welcome to stay. But it's highly likely that Langdon was paid scarcely more for these features than what he was receiving at Columbia for work in short subjects which required less time to shoot (although probably not much less). The meager salary and the extended shooting schedules would have made this a simple economic decision for Langdon, who continued to appear in more financially reasonable supporting roles. But it's a pity that Rogers and Langdon didn't continue as a team. Undeveloped as their partnership was, the spark for something better was there, something that cannot be said for Langdon's notorious teaming with Swedish dialect comic El Brendel at Columbia. And, as threadbare as these final starring features may be, they show that Langdon was in fine form well past his accepted prime. Despite weak stories, cheap sets, and lousy gags, Harry Langdon was funny to the end. Take that, Capra.

Happily for we obsessive comedy obscureologists, both Double Trouble and House of Errors are available on DVD from Grapevine Video for a mere 9.95 each. Even better, Misbehaving Husbands is available at archive.org for free. Truly, we live in a age of wonders.

Labels: Charley Rogers, cinema, Harry Langdon, Laurel and Hardy

1 Comments:

https://www.ipetitions.com/petition/please-release-the-non-stooge-columbia-shorts-to

Post a Comment

<< Home