"Tonight the show is gonna be different, Graham!"

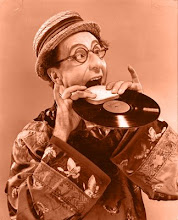

The catalyst for both the first great flowering of American radio and the tremendous popularity enjoyed by Wynn, Cantor, Pearl, et al, was the Great Depression. The nation’s seemingly insatiable hunger for escapist entertainment catapulted comics who specialized in “nut” acts to unprecedented heights of popularity. The sillier and the mo

McNamee: Chief, what did you do over the weekend?

Wynn: Oh, I took a vacation! I went down to the Atlantic Ocean, Graham. I had a room facing the ocean: the Pacific. I went on a two-day fishing trip, y’know.

McNamee: Catch any fish, Chief?

Wynn: Oh, well, the first day I was training the fish to eat off the hook, y’know..

McNamee: Any luck the second day?

Wynn: Well. I caught a flounder but I threw it right back, Graham.

McNamee: Why’d you throw a flounder back?

Wynn: (laughs) Well, I didn’t want a fish that had been stepped on, don’t y’see?

McNamee: The oyster season started down there last month, didn’t it, Chief?

Wynn: No, Graham, it started two months ago!

McNamee: You’re wrong, Chief. The oyster season begins in the first month that has an ‘R’ in it.

Wynn: That’s right.

McNamee: That’s September!

Wynn: No! What about R-gust?

McNamee: You can waste time catching your fish, Chief. I’ll buy mine in the market!

Wynn: Well, I’m glad you said ‘market’, Graham. Really, I’ve got a brand new song I want Don to play about the butcher… the market made me think of the butcher song... The name of it is “Butcher Arms Around Me”!

Ed Wynn, who also wrote the series, allowed it to develop organically. Unlike Joe Penner and Jack Pearl's catchphrases, the running gags and catchphrases on Wynn's Fire Chief program were usually the result of natural on-air flubs. Wynn's famous drawn out "so-o-o-o-o-o" line was initially a goof caused by mike fright that Wynn decided to retain because of the huge laugh it received. Likewise, Graham McNamee flubbed one of his Texaco sales pitches and referred to "Fire Chief gasoloon" leading to a long running gag. Also adding to the sense of naturalism on Wynn's show was his apparent impatience with McNamee's Texaco ads, a sentiment probably shared by most of the audience. Wynn would talk through the backgrounds of McNamee's Texaco pitches, interjecting comments such as "oh, there he goes again" and "You just said that, Graham!". Often, a joke would be worked into the sales pitch helping to make the ad more palatable and also to smooth over the transitions.

Ed Wynn, who also wrote the series, allowed it to develop organically. Unlike Joe Penner and Jack Pearl's catchphrases, the running gags and catchphrases on Wynn's Fire Chief program were usually the result of natural on-air flubs. Wynn's famous drawn out "so-o-o-o-o-o" line was initially a goof caused by mike fright that Wynn decided to retain because of the huge laugh it received. Likewise, Graham McNamee flubbed one of his Texaco sales pitches and referred to "Fire Chief gasoloon" leading to a long running gag. Also adding to the sense of naturalism on Wynn's show was his apparent impatience with McNamee's Texaco ads, a sentiment probably shared by most of the audience. Wynn would talk through the backgrounds of McNamee's Texaco pitches, interjecting comments such as "oh, there he goes again" and "You just said that, Graham!". Often, a joke would be worked into the sales pitch helping to make the ad more palatable and also to smooth over the transitions.In 1933, at the peak of his popularity, Ed Wynn was being tuned-in weekly by nearly half of the nation’s total radio audience, numbers beaten only by Amos N’ Andy, also being broadcast by NBC. But by 1935, the series had been cancelled and, for all intents and purposes, Ed Wynn's radio career was finished. Wynn's downfall has often been ascribed to audiences' rapidly changing tastes in comedy. By the time his Fire Chief program ended, America was warming to the character-based situation comedies of Jack Benny which offered not only gags but stories and large casts of characters. Wynn wasn't exactly incapable of making such a transition as he would later prove, but it never even seems to have occurred to him. All three of his 1935-37 follow-up series, Gulliver, Ed Wynn's Grab Bag, and The Perfect Fool, recycled the Fire Chief format of vaudeville patter and music. But just as likely to have killed Ed Wynn's radio career was the then-unknown concept of media saturation. 1933, Wynn's ratings peak, was also the year MGM released the gruelingly unfunny The Chief, starring Wynn and 'based' on the radio series. It was a legendary box office bomb, one of MGM's all-time worst comedies (and that's saying something!). At the same time, Wynn was making news by attempting to start his own radio network to put unemployed actors and actresses to work, a noble cause killed by financial mismanagement. I find it likely that by 1934, changing tastes or not, people were looking for excuses to not listen to Ed Wynn. Eager for something new, they moved on. Ed Wynn, however, couldn't. For Wynn, the latter half of the 30s were the darkest years of his life. Rejected by his audience, his marriage in ruins, and his star descending on Broadway, Wynn sank into a deep depression. A 1944-45 radio series, Happy Island, was an improvement over his previous network failures as it featured stories and a recurring cast of performers (including a young Jim Backus), but it received poor ratings and was off the air after only twenty-six weeks. It would be another four years before Ed Wynn was finally 'rediscovered' by the new medium of television.

To hear an episode of The Texaco Fire-Chief Program starring Ed Wynn for free, visit here.

Labels: Ed Wynn, Eddie Cantor, Jack Pearl, OTR

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home