Will Hay and his Comedy Divine - a Good-Looking Englishman's Perspective

Well, after Aaron's article, what else could I call it?

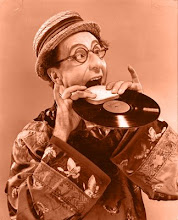

Will Hay's entitlement to Third Banana status is fully justified, even in sleepy old England. Most of his movies are available on DVD here with the exception of some early ones and the elusive single-print Fox masterpiece Where's That Fire? - but they hardly ever appear on television, so poor old Will is just as obscure now in his native land as the rest of his contemporaries. It has to be said, though, that he's always been regarded over here as a bit special; it's rare indeed for a middle-aged comedian with such non-existent romantic appeal to have such a successful film career. As Aaron points out, this has much to do with the fact that Hay is always a real person. Apart from his closing remarks to the audience in The Ghost of St. Michael's, he's always within the film, earnestly but inefficiently trying to get on with whatever job he has to do in the mistaken belief that his superiors are blind to his ineptitude, while simultaneously using whatever nominal authority he has in order to generate a bit of extra cash for himself through some minor scam. Unlike Robb Wilton, another comedian who specialized in bumbling officialdom, Will knows deep down inside that he's been promoted far beyond his capabilities, but he feels that he's sharp enough to bluster his way out of trouble if his failings are exposed. His subordinates, insolent fat teenager Graham Moffatt ("Albert") and venerable rascal Moore Marriott ("Harbottle"), if anything even more dishonest than Hay himself, are quite happy to rob and blackmail him, and each other, if the opportunity arises. We've all known people like this.

This, then, is The Secret of Will Hay: he was a great actor as well as a great comedian. He doesn't seem to be acting at all, never appears to be trying to be amusing. It's the art that conceals art. Kenneth Williams knew this; he was flamboyant and artificial, which explains his deep dislike for Sid James who turned up and gave a flawless reading of the lines with the minimum of apparent effort, so he could get paid and get on the phone to the bookie. And let's not forget the obvious fact that Moffatt and Marriott were Hay's equal in film technique.

So, yes, Hay, Moffatt and Marriott are the British equivalent of the Marx Brothers; far more acceptable candidates than the usual contenders for the title, the Crazy Gang. The Gang, three mid-life double-acts of variable quality (Flanagan and Allen at one end of the scale; Naughton and Gold very definitely at the other) made their movies at the

Aaron mentioned the reluctance of the American film companies to give Stateside promotion to the product of their own British studios (another example being the Max Miller's War

When the Marx Brothers tried to play Real Human Beings they produced things like Room Service. Don't misunderstand me; I think the Marxes are wonderful. Hay, Moore and Marriott, equally wonderful, brought about their anarchy from inside the real world, by undermining stuffy old 1930s England where order and efficiency mattered. Did it really? Or were we a suppressed nation, waiting for all that dull Ealing-type crap to get out of the way so we could get to the 1960s? Will Hay was the most popular English comedian of his time, and I believe this is because (a) the crafty old bugger was absolutely real, and (b) we'd all like to be as devious and shifty and sloppy as he is and (c) get away with it. If Ask a Policeman has a flaw, this is it: Hay and his pals don't get away with it. In Where's That Fire? they do.

There's not enough space in this one article to discuss Hay's early movies, before he encountered the Dynamic Duo, but they're mostly unsuccessful attempts at trying to find a "persona" for him. Three or four films in, someone realized it was there all the time: the seedy schoolteacher was adaptable to any kind of tatty authority. Needless to say, in these early efforts Hay's acting is always exemplary, even when he isn't funny at all (as in Radio Parade of 1935).

Ditching Moffatt and Marriott was probably the greatest mistake of Hay's career; but on the basis of the six movies he made with them, he's entitled to eternal membership of the Third Banana. So move over Ted, Joe, Bert, Cliff... and let another Englishman join your ranks. And what will be his first words on arrival? He'll peer over his glasses, give everybody the Dreaded Stare, sniff, shrug his shoulders and say:

"Good morning, boys!"

Labels: cinema, Edgar Kennedy, Moffatt and Marriott, Will Hay

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home