That's Me All Over

by Geoff Collins

My absence from this site over the last couple of weeks has been a product of two factors: a busy period at work [who's he kidding?] and the heatwave which is gripping the whole of England like a bulldog's teeth around a postman's tackle. With temperatures soaring to 36 degrees centigrade, who wants to spend an evening in front of Rubberlegs the Useless Computer? That's Me All Over the Sofa is more like it. My cat Hodge, sprawled out over the floor with his tongue hanging out, looks as if he's been dropped from a great height. His only movement is an occasional tail-flick, as if to say "I'm still alive; don't put me in the bin-bag yet."

Excuses over. When I haven't been sitting in the garden after a hard day at The Finest Art Gallery Outside London [www.cecilhigginsartgallery.org - haven't mentioned them for a while!] with a cool toddy, I've been wading through some recently acquired DVDs, by coincidence most of them the product of Whitebread City, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. "Product" is exactly right of course. I've been a bit harsh about this studio in the past, and I haven't finished yet, but even this prestigious, conventional studio could come up with a few surprises. Here's one:

At the end of his "Singin' in the Rain" routine, Gene Kelly kindly gives his umbrella to a wet little man scurrying along the street. This is Snub Pollard; and it's an interesting thought that he could be playing himself here in this "1927-28 Hollywood", rushing home after another frustrating day at Weiss Brothers, churning out cheapo shorts with Martin Loback in a pathetic attempt to emulate the success of Stan and Ollie. Poor Snub. Think of him the next time you watch this wonderful number, and you'll find it's about Snub, not Gene. He's hardly recognizable, a bit player; yet he represents what really happened to a lot of people when sound came in.

At the end of his "Singin' in the Rain" routine, Gene Kelly kindly gives his umbrella to a wet little man scurrying along the street. This is Snub Pollard; and it's an interesting thought that he could be playing himself here in this "1927-28 Hollywood", rushing home after another frustrating day at Weiss Brothers, churning out cheapo shorts with Martin Loback in a pathetic attempt to emulate the success of Stan and Ollie. Poor Snub. Think of him the next time you watch this wonderful number, and you'll find it's about Snub, not Gene. He's hardly recognizable, a bit player; yet he represents what really happened to a lot of people when sound came in.

Dusty old comedy is full of such surprises. In previous articles we've discussed the likelihood that many comedy sketches, even individual gags, frequently pre-date their accepted points of origin. Thus "Abbott and Costello" routines were being performed by the English double-act Collinson and Dean ten years earlier (the proof is on www.britishpathe.com; and check out Aaron's astute article on these guys in our Archive). Bill Collinson brought a load of "borrowed" American comedy back from his vaudeville tours in the 1920s, so this material probably dates from a lot earlier than this. "Keep the fire going till we get there" is a gag which has been traced from the first draft of A Day At the Races, via Robb Wilton, and as far back as Dan Leno, 1901. Authorship of the "cheap tailor" sketch "Belt in the Back", as seen in Glorifying the American Girl, was even the subject of a lawsuit [with a belt in the back?] between Cantor and Hearn, as detailed in Variety of May 11, 1949 and one of my previous articles. You'd think the subject would be exhausted by now - or I would. Wrong!

Tolerance of The Wizard of Oz past the endless, soul-destroying Munchkin sequence will reveal a treasure-trove of interpolated lines by the three giants of vaudeville, Third Bananas all, who accompany Dorothy on her journey. Not surprisingly Bert Lahr has the Lion's share. For example, when they all wake up in a snowstorm, he comments absent-mindedly "Unusual weather we're havin', ain't it?" Much-quoted, it's true, but we can't have enough of this seriously-underfilmed genius. This example almost passed me by; but it rang some familiar bells:

(and he might have added "Gnong gnong gnong !" but he didn't. You can't have everything.)

....which all goes to show that this unique and original film isn't all that unique and original. Here's an earlier version of the same gag, excerpted in To See Such Fun. It's unattributed but my guess is that it's from Hold My Hand (1938):

To See Such Fun is a 1977 compilation of scenes from fifty years of British film comedy. It's all in black-and-white, even the colour clips - presumably in a well-meaning attempt to prevent eyestrain - and despite some ferociously choppy editing it gives us the chance to see a lot of fantastic archive material and some incredibly rare Third Bananas. Stanley Lupino's already been mentioned on this site, and will be again, dear readers, I promise you, for he is the Thirdest Banana of all. His version of this venerable gag is placed alongside - and uncharitably edited into - a version from Radio Parade of 1935, which is performed by Haver and Lee.

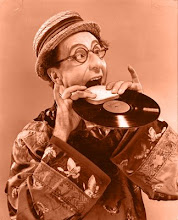

"Haver" is American-accented, tall, bespectacled and annoyed. During World War Two he was "Clay Keyes", host of a radio variety show "The Old Town Hall". "Lee" is a small, baggy-trousered Chaplinesque Englishman. They must be the most obscure double-act in the whole of British music-hall history; I don't even know their first names, or what became of them. One thing is certain: they outclass all the movie's other acts, who are all professional entertainers pretending to be "talented amateurs", but actually coming across as untalented amateurs. Was British variety really this bad?

annoyed. During World War Two he was "Clay Keyes", host of a radio variety show "The Old Town Hall". "Lee" is a small, baggy-trousered Chaplinesque Englishman. They must be the most obscure double-act in the whole of British music-hall history; I don't even know their first names, or what became of them. One thing is certain: they outclass all the movie's other acts, who are all professional entertainers pretending to be "talented amateurs", but actually coming across as untalented amateurs. Was British variety really this bad?

Hardly. Radio Parade of 1935 is a flashy Art-Deco sequel to the 1933 Radio Parade, a far less stylish film which preserved some far superior talents [and despite the loss of the first reel, it's available for viewing on www.britishpathe.com. Type in "Claude Hulbert" for access to all of it]. The 1935 edition, ballyhoo and obnoxious colour sequences notwithstanding, is obviously the second team. Will Hay, who looks just like Boris Karloff here, should have carried his impersonation a stage further and killed them all off, one by one.

Righto, as we're supposed to say over 'ere: Third Banana readers, it's over to you. Tell us more about Haver and Lee. Their bleak, aggressive crosstalk is far from the cosy warmth of the British double-acts such as Flanagan and Allen, and as such, they stand out as something fresh and different. What became of them? Why didn't they appear in other films, newsreels or recordings? [Pathe has a couple of juicy clips which I'll download when Rubberlegs lets me; but if your computer has been manufactured since 1960 you should be able to view these]. And one final question: who wrote "That's me all over"? We'd love to come across an even earlier version, which just goes to show how sad we really are.

That's me all over - until it gets a bit cooler anyway. Goodnight.

My absence from this site over the last couple of weeks has been a product of two factors: a busy period at work [who's he kidding?] and the heatwave which is gripping the whole of England like a bulldog's teeth around a postman's tackle. With temperatures soaring to 36 degrees centigrade, who wants to spend an evening in front of Rubberlegs the Useless Computer? That's Me All Over the Sofa is more like it. My cat Hodge, sprawled out over the floor with his tongue hanging out, looks as if he's been dropped from a great height. His only movement is an occasional tail-flick, as if to say "I'm still alive; don't put me in the bin-bag yet."

Excuses over. When I haven't been sitting in the garden after a hard day at The Finest Art Gallery Outside London [www.cecilhigginsartgallery.org - haven't mentioned them for a while!] with a cool toddy, I've been wading through some recently acquired DVDs, by coincidence most of them the product of Whitebread City, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. "Product" is exactly right of course. I've been a bit harsh about this studio in the past, and I haven't finished yet, but even this prestigious, conventional studio could come up with a few surprises. Here's one:

At the end of his "Singin' in the Rain" routine, Gene Kelly kindly gives his umbrella to a wet little man scurrying along the street. This is Snub Pollard; and it's an interesting thought that he could be playing himself here in this "1927-28 Hollywood", rushing home after another frustrating day at Weiss Brothers, churning out cheapo shorts with Martin Loback in a pathetic attempt to emulate the success of Stan and Ollie. Poor Snub. Think of him the next time you watch this wonderful number, and you'll find it's about Snub, not Gene. He's hardly recognizable, a bit player; yet he represents what really happened to a lot of people when sound came in.

At the end of his "Singin' in the Rain" routine, Gene Kelly kindly gives his umbrella to a wet little man scurrying along the street. This is Snub Pollard; and it's an interesting thought that he could be playing himself here in this "1927-28 Hollywood", rushing home after another frustrating day at Weiss Brothers, churning out cheapo shorts with Martin Loback in a pathetic attempt to emulate the success of Stan and Ollie. Poor Snub. Think of him the next time you watch this wonderful number, and you'll find it's about Snub, not Gene. He's hardly recognizable, a bit player; yet he represents what really happened to a lot of people when sound came in.Dusty old comedy is full of such surprises. In previous articles we've discussed the likelihood that many comedy sketches, even individual gags, frequently pre-date their accepted points of origin. Thus "Abbott and Costello" routines were being performed by the English double-act Collinson and Dean ten years earlier (the proof is on www.britishpathe.com; and check out Aaron's astute article on these guys in our Archive). Bill Collinson brought a load of "borrowed" American comedy back from his vaudeville tours in the 1920s, so this material probably dates from a lot earlier than this. "Keep the fire going till we get there" is a gag which has been traced from the first draft of A Day At the Races, via Robb Wilton, and as far back as Dan Leno, 1901. Authorship of the "cheap tailor" sketch "Belt in the Back", as seen in Glorifying the American Girl, was even the subject of a lawsuit [with a belt in the back?] between Cantor and Hearn, as detailed in Variety of May 11, 1949 and one of my previous articles. You'd think the subject would be exhausted by now - or I would. Wrong!

Tolerance of The Wizard of Oz past the endless, soul-destroying Munchkin sequence will reveal a treasure-trove of interpolated lines by the three giants of vaudeville, Third Bananas all, who accompany Dorothy on her journey. Not surprisingly Bert Lahr has the Lion's share. For example, when they all wake up in a snowstorm, he comments absent-mindedly "Unusual weather we're havin', ain't it?" Much-quoted, it's true, but we can't have enough of this seriously-underfilmed genius. This example almost passed me by; but it rang some familiar bells:

Scarecrow: Help! Help! Help!

Tin Man: Well, what happened to you?

Scarecrow: They tore my legs off and they threw them over there! Then they

took my chest out and they threw it over there!

Tin Man (indignant): Well, that's you all over!

Cowardly Lion: They sure knocked the stuffin's outa ya, didn't they?

(and he might have added "Gnong gnong gnong !" but he didn't. You can't have everything.)

....which all goes to show that this unique and original film isn't all that unique and original. Here's an earlier version of the same gag, excerpted in To See Such Fun. It's unattributed but my guess is that it's from Hold My Hand (1938):

Bad Guy (ferociously): I could pick you up and throw you north, south, east and west!

Stanley Lupino (nonchalantly laughs): Heh heh heh! That's me all over! (adjusts his tie as he walks away)

To See Such Fun is a 1977 compilation of scenes from fifty years of British film comedy. It's all in black-and-white, even the colour clips - presumably in a well-meaning attempt to prevent eyestrain - and despite some ferociously choppy editing it gives us the chance to see a lot of fantastic archive material and some incredibly rare Third Bananas. Stanley Lupino's already been mentioned on this site, and will be again, dear readers, I promise you, for he is the Thirdest Banana of all. His version of this venerable gag is placed alongside - and uncharitably edited into - a version from Radio Parade of 1935, which is performed by Haver and Lee.

Haver (with appropriate gestures): One of these days I'll lose my temper with you, and I'll take a hold of your arms and I'll break 'em over there and throw 'em over there! Then I'll get a hold of your legs and I'll break 'em over here and throw 'em over there! Then I'll get your head and crrrush it up, right up like that, and throw it back there! Whadda ya think of that?

Lee (sad, resigned to his fate): That's me all over!

"Haver" is American-accented, tall, bespectacled and

annoyed. During World War Two he was "Clay Keyes", host of a radio variety show "The Old Town Hall". "Lee" is a small, baggy-trousered Chaplinesque Englishman. They must be the most obscure double-act in the whole of British music-hall history; I don't even know their first names, or what became of them. One thing is certain: they outclass all the movie's other acts, who are all professional entertainers pretending to be "talented amateurs", but actually coming across as untalented amateurs. Was British variety really this bad?

annoyed. During World War Two he was "Clay Keyes", host of a radio variety show "The Old Town Hall". "Lee" is a small, baggy-trousered Chaplinesque Englishman. They must be the most obscure double-act in the whole of British music-hall history; I don't even know their first names, or what became of them. One thing is certain: they outclass all the movie's other acts, who are all professional entertainers pretending to be "talented amateurs", but actually coming across as untalented amateurs. Was British variety really this bad?Hardly. Radio Parade of 1935 is a flashy Art-Deco sequel to the 1933 Radio Parade, a far less stylish film which preserved some far superior talents [and despite the loss of the first reel, it's available for viewing on www.britishpathe.com. Type in "Claude Hulbert" for access to all of it]. The 1935 edition, ballyhoo and obnoxious colour sequences notwithstanding, is obviously the second team. Will Hay, who looks just like Boris Karloff here, should have carried his impersonation a stage further and killed them all off, one by one.

Righto, as we're supposed to say over 'ere: Third Banana readers, it's over to you. Tell us more about Haver and Lee. Their bleak, aggressive crosstalk is far from the cosy warmth of the British double-acts such as Flanagan and Allen, and as such, they stand out as something fresh and different. What became of them? Why didn't they appear in other films, newsreels or recordings? [Pathe has a couple of juicy clips which I'll download when Rubberlegs lets me; but if your computer has been manufactured since 1960 you should be able to view these]. And one final question: who wrote "That's me all over"? We'd love to come across an even earlier version, which just goes to show how sad we really are.

That's me all over - until it gets a bit cooler anyway. Goodnight.

Labels: Bert Lahr, cinema, Collinson and Dean, Haver and Lee, Snub Pollard, Stanley Lupino