The Mancunian Candidate

by Geoff Collins

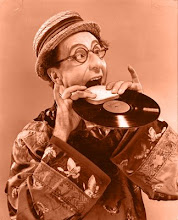

Can you handle any more of Randle? To illustrate my previous article on the wily Lancastrian comedian Frank Randle, our own wily Texan blogmeister Aaron managed to unearth a couple of appropriate clips. Now we're pleased to announce that he has the whole of It's a Grand Life to play with. This 1953 epic is of epic length - nearly two hours - and it was Randle's last film, the one which reveals him as a man on the brink, just before he allowed his personal demons to ruin his career and his life. For as we have discussed before, Randle's comic persona of barely coherent insolence was fuelled by real-life psychosis, depression and alcoholism. On a good day, he could be generous and kind; at other times he made Lou Costello look like Little Bo Peep.

Most of Randle's pictures were made by Mancunian, a provincial unit specializing in cheap comedies for Northern audiences. They're overlong, dreary and unbelievably inept as examples of film-making, and many only survive in heavily-cut reissue versions, which, perversely, sharpens them up and improves their quality as movies. The advantage of producer/director John Blakeley's "put it in front of a camera and shoot it" method is that we're left with a lot of long, uninterrupted comedy routines. Good!

You may recall that I attempted (!) to transcribe one of Randle's routines from this film, the sequence in which he's being forced to explain why he allowed the deserter Barnes to escape. What his superior officers fail to realize is that you don't force Frank Randle to do anything, any more than you would attempt to do so with Frank Sinatra. While remaining outwardly subservient and apologetic - after all, he IS getting an almighty telling-off - Randle shows these mundane inhabitants of Planet Army that it doesn't bother him one little bit. Like Jeff Nuttall in King Twist, I didn't manage to transcribe this scene with full accuracy and missed the brief gallstones-slop stones gag, which seems to have been a favorite: Duggie Wakefield uses it in The Penny Pool. Anyway, for the benefit of America and anyone else reading and watching, this is Frank Randle at full speed.

A bit later in the movie there's another scene which I found impossible to transcribe due to all the overlapping dialogue, although I suspect every last syllable was worked out in advance. You may be familiar with the films of Will Hay (check out our archive): incompetent blowhard Hay failing to maintain any kind of order while constantly bickering with disrespectful teenage chubster Graham Moffatt and crafty codger Moore Marriott. This scene from It's a Grand Life brings the concept to a new level - and you must decide for yourself whether the level is higher or lower. It's well documented that John E. Blakeley disparagingly dismissed any kind of witty dialogue as "London comedy"; he personally preferred slapstick, or anything that involved people falling over. In this provincial variation on the Hay-Moffatt-Marriott setup, Randle, although absolutely basic as a human being, is still sharp enough to rob the gullible rookie twice.

One of the most beloved of all comedy situations on both sides of the Atlantic in the forties and fifties was the Drill Routine. Abbott and Costello performed it beautifully in Buck Privates, Jewel and Warriss copied it very badly in What a Carry On (Mancunian, 1949) and there's a peculiar early version in which soppy Jack Haley mysteriously attempts to behave like one of the Bowery Boys (Saltwater Daffy, Vitaphone 1933; don't fret, readers, we'll get to it). Any number of comedians have portrayed the hapless new recruit at the mercy of a bullying drill sergeant; Randle's variation was to make his character anarchic and disruptive while apparently attempting to be helpful. All Sergeant Michael Brennan can do is stand back and let it all happen. Technical query: after Randle belches and complains of "a touch of wind", does he fart as well? Or is that (a) a buzz on the sound track or (b) wishful thinking on my part?

And finally, Impersonating an Officer, in which Randle delivers a long lecture while managing to explain absolutely nothing at all and trying to interest the gorgeous Diana Dors in his bazooka. I don't blame him. You'll notice that the "romantic lead", for possibly the only time in a Mancunian film, isn't a complete wimp and gets quite energetically involved in the comedy. Bravo John Blythe!

We've attempted to pick the best scenes from It's a Grand Life - which is a far from perfect movie - in order to give you a flavour of what this erratic and willful comedian was all about. Love him or loathe him, Frank Randle was unique. He played his part in extending the bounds of comedy - and also, very likely, the bounds of good taste. Enjoy these glimpses of the disgraceful old rascal at his very best.

Can you handle any more of Randle? To illustrate my previous article on the wily Lancastrian comedian Frank Randle, our own wily Texan blogmeister Aaron managed to unearth a couple of appropriate clips. Now we're pleased to announce that he has the whole of It's a Grand Life to play with. This 1953 epic is of epic length - nearly two hours - and it was Randle's last film, the one which reveals him as a man on the brink, just before he allowed his personal demons to ruin his career and his life. For as we have discussed before, Randle's comic persona of barely coherent insolence was fuelled by real-life psychosis, depression and alcoholism. On a good day, he could be generous and kind; at other times he made Lou Costello look like Little Bo Peep.

Most of Randle's pictures were made by Mancunian, a provincial unit specializing in cheap comedies for Northern audiences. They're overlong, dreary and unbelievably inept as examples of film-making, and many only survive in heavily-cut reissue versions, which, perversely, sharpens them up and improves their quality as movies. The advantage of producer/director John Blakeley's "put it in front of a camera and shoot it" method is that we're left with a lot of long, uninterrupted comedy routines. Good!

You may recall that I attempted (!) to transcribe one of Randle's routines from this film, the sequence in which he's being forced to explain why he allowed the deserter Barnes to escape. What his superior officers fail to realize is that you don't force Frank Randle to do anything, any more than you would attempt to do so with Frank Sinatra. While remaining outwardly subservient and apologetic - after all, he IS getting an almighty telling-off - Randle shows these mundane inhabitants of Planet Army that it doesn't bother him one little bit. Like Jeff Nuttall in King Twist, I didn't manage to transcribe this scene with full accuracy and missed the brief gallstones-slop stones gag, which seems to have been a favorite: Duggie Wakefield uses it in The Penny Pool. Anyway, for the benefit of America and anyone else reading and watching, this is Frank Randle at full speed.

A bit later in the movie there's another scene which I found impossible to transcribe due to all the overlapping dialogue, although I suspect every last syllable was worked out in advance. You may be familiar with the films of Will Hay (check out our archive): incompetent blowhard Hay failing to maintain any kind of order while constantly bickering with disrespectful teenage chubster Graham Moffatt and crafty codger Moore Marriott. This scene from It's a Grand Life brings the concept to a new level - and you must decide for yourself whether the level is higher or lower. It's well documented that John E. Blakeley disparagingly dismissed any kind of witty dialogue as "London comedy"; he personally preferred slapstick, or anything that involved people falling over. In this provincial variation on the Hay-Moffatt-Marriott setup, Randle, although absolutely basic as a human being, is still sharp enough to rob the gullible rookie twice.

One of the most beloved of all comedy situations on both sides of the Atlantic in the forties and fifties was the Drill Routine. Abbott and Costello performed it beautifully in Buck Privates, Jewel and Warriss copied it very badly in What a Carry On (Mancunian, 1949) and there's a peculiar early version in which soppy Jack Haley mysteriously attempts to behave like one of the Bowery Boys (Saltwater Daffy, Vitaphone 1933; don't fret, readers, we'll get to it). Any number of comedians have portrayed the hapless new recruit at the mercy of a bullying drill sergeant; Randle's variation was to make his character anarchic and disruptive while apparently attempting to be helpful. All Sergeant Michael Brennan can do is stand back and let it all happen. Technical query: after Randle belches and complains of "a touch of wind", does he fart as well? Or is that (a) a buzz on the sound track or (b) wishful thinking on my part?

And finally, Impersonating an Officer, in which Randle delivers a long lecture while managing to explain absolutely nothing at all and trying to interest the gorgeous Diana Dors in his bazooka. I don't blame him. You'll notice that the "romantic lead", for possibly the only time in a Mancunian film, isn't a complete wimp and gets quite energetically involved in the comedy. Bravo John Blythe!

We've attempted to pick the best scenes from It's a Grand Life - which is a far from perfect movie - in order to give you a flavour of what this erratic and willful comedian was all about. Love him or loathe him, Frank Randle was unique. He played his part in extending the bounds of comedy - and also, very likely, the bounds of good taste. Enjoy these glimpses of the disgraceful old rascal at his very best.

Labels: cinema, Frank Randle