The Marx Brothers are on a fire engine, racing through the city streets. As they pass a genuine fire, Groucho yells "Keep it going till we get back!"

It's a wonderful gag, and writer Joe Adamson has expressed quite valid regret that it never made it into the final version of the much-rewritten

A Day At the Races. But thanks to the gently repetitive nature of classic comedy, wherein gags are often half-remembered and re-cycled, we've managed to locate three earlier variations. Maybe, dear readers, you can provide some more.

In the 1935 Vitaphone short

His First Flame, fire chief Donald MacBride has

forbidden any fires to take place because the fire station is being used for Shemp and Daphne's wedding. A weedy Skelton-like fireman (Fred Harper??) answers the phone. There's a fire. He informs the chief but is bawled out. Back on the phone to the distraught caller, he says ""Well, keep it burning a little while longer. Yeah, yeah....I tried to tell him but he wouldn't listen...." Naturally it's the chief's house that's on fire.

Several years earlier, another barely-competent fire chief, Robb Wilton, has his opening monologue interrupted by a frantic woman (Florence Palmer) whose house is burning down. After some attempts at helpful pleasantries ("Turned out nice again, hasn't it?") Robb endeavours to summon his lads via his archaic speaking-tube. He sends Flo back to the fire: "Don't wait now, lady, just slip along - ask 'em to keep it goin' a bit, will yer?"

Robb filmed his fire station sketch for Pathe in 1934, recorded it on a Sterno 78 on September 24, 1931 (see

www.pavilionrecords.com) and was performing it for several years before this. But we have an earlierversion...

much earlier.

It's a tricky business, writing about the great comedians of yesteryear. There's usually somebody still living who remembers your subject, and they can say "No - you're wrong! He wasn't like that at

all!" In the case of Dan Leno, no such problem arises. Dan was born on December 20, 1860 and died on October 31, 1904. He's been dead over a hundred years. Yet in a curious way it seems as if he's still around, haunting us. He's certainly supposed to haunt the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (he was the Phantom of the Operetta). Stanley Lupino, who was into spiritualism, always maintained that he saw Dan's ghost. And Dan himself, in his photographs, has a haunting, haunted look, quite unsettling. You

know that this man was no run-of-the-mill comic.

Dan Leno was considered to be the greatest music-hall comedian of the late nineteenth century, the Funniest Man on Earth. He was a quirky little London-Irish sprite, crumpled and sometimes mournful but always eager, alert and resilient. A tiny Milligan, forty years ahead of his time, his material often wandered off into completely unexpected areas which must have baffled the more prosaic members of his audience. He was praised by contemporary writers such as W. MacQueen Pope whose florid, anecdotal excess makes him the most appropriately named writer in the history of literature. But where's our hard evidence? Where's the living Dan?

The good news is: Dan made some films. The bad news is: none of them exist. Dan was around at the very beginning of the film industry, long before "preservation" was even considered. The early films were ephemeral and disposable; any survivals from this early date are purely accidental. A brief sequence was recently unearthed, showing Dan and his wife Lydia having fun at a garden fete. It's in the form of a portable Kinora "what the butler saw" paper flip book: a miraculous discovery - but not really representative.

So here's some more good news: Dan made nearly thirty recordings. But the bad news is: they're over a hundred years old,

very scratchy and recorded at bewilderingly inconsistent speeds. Before 78 rpm was recognised as the most effective speed, it was every man for himself. Dan's record of "Going To the Races" (Gramophone and Typewriter GC2-2808) was made at about 65 rpm, as I discovered when I first played my battered old copy at 78 and got an incomprehensible high-pitched chirping. I had to hold my finger on the turntable to find out what it was all about.

More bad news: Dan wasn't happy with the primitive recording process, specifically the

lack of an audience ("How can I be funny into a funnel?") so there's always a slight self-consciousness. Good news: when a record's a hundred years old, this hardly matters. We're lucky to have

anything by Dan Leno; and as the record industry was in its infancy, there are few retakes and all the little fluffs are left in. For example : Dan usually starts and finishes with something resembling a brisk little song, as a framework for his character patter. Here's the first line of the

published chorus of "The Beefeater":

"It's a splendid place to spend a happy day..."

On Dan's record "The Tower of London" (matrix 1129) this is what he sings :

"For it's a splendid time to see the happy hour..."

... so the next line doesn't rhyme. Annoyed at being caught off guard, right at the end of the record Dan says "

No!"

Dan's very first record was "Who Does the House Belong To?", made at the Maiden Lane offices of Gramophone and Typewriter in November 1901. After a quick piano-accompanied chorus of the song, he launches into a monologue about some wonderful property he's just bought; it gradually becomes apparent that the place is a total wreck. Unfortunately the record runs out before he's finished, and clearly he's not pleased when the engineer points this out.

Dan: .... there's a little bit of garden at the bottom, you know, and I think a bit of garden looks lovely. It runs from the house...down to the river. The river's at the bottom of the garden... one month out of the year. The rest of the time, the garden's at the bottom of the river. Because the river...like, er... flows. It's, er, really the gasworks, the overflow from the gasworks, that's what it is. But it looks pretty when the sun shines on it, with all the pretty colours. But it's , er, through the wife that I bought this other house, that I haven't paid for. She came home one day, and she said, er..."why pay rent?" "Well" I said, "darling, I don't know that we have been very guilty up to the present." She said, er..."Read that", and I read it. And it said "Money advanced...without security." I said "well, that'll suit me down to the ground." [pause] [to engineer] Is that it?

Engineer: [distant undecipherable mutterings]

Dan: Chorus ?

Engineer: [more muttering]

Dan: Suit me down to the ground.

Engineer: [mutter mutter]

Piano accompanist: [starts to play the chorus again, then stops. More muttering as the record runs out]

How rare is this? A fragment of an Edwardian

argument, captured forever.

Still more good news: nineteen of Dan's recordings, oddly including the

sequel to "Going to the Races" (02001) but not the original, are available on CD from www.musichallcds.com. The sound quality is excellent. Every word is audible and they all seem to have been transferred at about the correct speed, which is not always the case in reissues of ancient material; so we can experience the pleasure of Dan's ramblings as "The May Day Fireman", in which Dan's voluntary fire brigade appears to be run with just as much efficiency as Robb Wilton's. Watch out for a line we discussed earlier!

You know, when you start a thing like this, there's a lot of trouble occurs. You know, I told the four boys with me...we've been out of work for over a twelvemonth, because they pulled the house down where we used to stand at the corner...but I told them, I said, we can make a lot of money by being a small fire brigade. I said, I'll pop up and see the superintendent. So I went up, and I said to 'im, er...he was in his office, I said, er....my idea was that we could be of some assistance. I said, erm...course, er, there was only one fire brigade in the village, that was his. And if a fire broke out at both ends of the village, it'd be impossible for him to squirt from one end to the other. So I...I told him, it was my idea, I said, we could be of some service, I said, a sort of little aide-de-camp brigade, I said, and if you had any little fires which you didn't want to attend to, I said, we can pop round and keep 'em going until you come up, you see. Course, he could see me idea, a very nice man he was, he never answered me. And I waited for about a half an hour outside. And, er...you see, my idea was this: not so much the fires...as the salvage. I said, we can, I told the boys, I said, we could pop round, while the fire's on, and look...look for salvage, er, see? Or, I said, we could go before there's a fire and find a bit of salvage somewhere. Or I said, perhaps in the middle of the night we could go... into houses and look round and make ourselves acquainted so that if there's a fire we, er, don't come up as strangers. So Butterworth turned round and said "Why not be burglars?" Now, you know, Butterworth's got no brains....

The justification of petty dishonesty is reminiscent of Will

Hay and his equipment-stealing crew in

Where's That Fire? But Dan's record was made forty years earlier; and there are no obvious "music-hall jokes". He performs the whole thing conversationally, in character, in his crisp "London with a dash of Dublin" voice. It's still funny today. Well, I think so, anyway.

In 1899 there appeared "Dan Leno - His Booke", a semi-autobiographical fantasy apparently written by the man himself, and full of the same off-at-a-weird-tangent material as the records. When a truncated, inaccurate reprint appeared in 1968, a 99-year-old hack called Tom C. Elder came out of the woodwork and claimed authorship for himself. To me this is just as disappointing as the occasion when the radio actor Norman Shelley (memorably described by Kenneth Williams as "that bogus old crapmound") declared that he'd recorded all of Churchill's wartime speeches. In my opinion, Dan's book is pure Dan. It

sounds like him, and I doubt if any mundane ghost writer (we're into "hauntings" again) could have come up with such a flow of free-form surrealism. The photographs were supplied by Dan, some of the cartoons are by Dan, and I'd dearly love to think that the whole thing is his. It's possible, of course, that it's a collaboration, or an "as told to". Did Elder just write it all down ? Or was he an unheralded scriptwriter? Let's argue! Incidentally, one of my most treasured books is a copy of the 1904 paperback edition, found in a car boot sale in Northampton in 1995. Miracles can still happen.

But here's the ultimate bad news. By 1904 Dan's health had collapsed. The strain of thirty-five years of continual hard work caught up with him. A major breakdown was followed by brief periods of partial recovery, but he was just worn out, and he died at the age of forty-three.

Dan died at Halloween; he haunts Drury Lane. Roy Hudd moved into Dan's house without knowing it had belonged to Dan; and Dan's leprechaun-like face, deep-eyed, sad and yet mischievious, still gazes at us out of the old photographs. A face like no other. We

know, just to look at him, that he was the great comedian they all said he was.

Yet the films continue to elude us. That would be the final treat.

But wait...let's take a look at

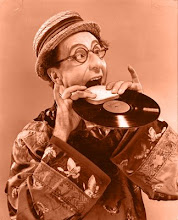

The Big Swallow, a short film made by James Williamson in about 1901. Just over a minute long, this was an incredibly original effort for its time. A small, dapper man is annoyed with a cameraman (offscreen) who is intent on taking his photograph. Thrashing about with his cane and insisting "I won't! I won't!" the man advances towards the screen into a terrifying close-up, and "swallows" the cameraman who is seen disappearing into the huge abyss of his cake-hole; then the film reverts slowly back to the medium-shot as the man is seen licking his lips contentedly. He gives us a big grin. Then the film ends.

But who's the star of this little movie? He wears a hat so we can't see his hairline. Initially he looks like Derek Jacobi; and that smile at the end is strikingly similar to a publicity picture of the comedian Charles Austin. But my immediate impression on first seeing the film was: "That's Dan Leno!"

All I ask, film historians amongst you, is one thing:

don't prove me wrong.