Who's Faultin' Maltin?

Marxian Madness: "a treat for their fans" - which is a much-used euphemism for "everyone else, including us, thinks it stinks". I just treated myself (because nobody else would) to the six-volume DVD set "The Marx Brothers Collection" which includes all of the Brothers' MGM movies plus A Night in Casablanca, along with numerous "special features" including - and this is what attracted me to the set - a whole bunch of MGM shorts from the same period. No Healys, alas, but there's an Our Gang, a couple of Pete "Annoying Wise Guy Narration" Smith Specialties, Robert Benchley in How To Sleep and A Night At the Movies, and a Warner Bros. Joe McDoakes. There's also James FitzPatrick droning on about the delights of San Francisco. His stodgy travelogues must have discouraged travel of any sort; they bored audiences for years but you need to sit through at least one of them to appreciate the Peter Sellers parody version Balham - Gateway to the South.

So what else could I do? I had to buy it; it was irresistible [and speaking of irresistible, who's the actress playing Benchley's wife in A Night At the Movies? She's the most alluring woman I've seen in my whole life.]

Only A Night At the Opera and A Day At the Races have commentaries, which isn't surprising: how could anyone be enthusiastic about At the Circus for an hour and a half? The funniest thing in the film is Groucho's toupee; and perversely it's also the saddest thing (apart from the lack of comedy and the fact that it's so obvious that nobody cared any more by this time). Why did they make him wear it? Why didn't he resist? How does it stay on his head when he

Only A Night At the Opera and A Day At the Races have commentaries, which isn't surprising: how could anyone be enthusiastic about At the Circus for an hour and a half? The funniest thing in the film is Groucho's toupee; and perversely it's also the saddest thing (apart from the lack of comedy and the fact that it's so obvious that nobody cared any more by this time). Why did they make him wear it? Why didn't he resist? How does it stay on his head when he  hangs upside-down with Eve Arden? Why doesn't it fall off when he hangs upside-down with Eve Arden? (At least he'd get one laugh) why is he hanging upside-down with Eve Arden? So many questions....

hangs upside-down with Eve Arden? Why doesn't it fall off when he hangs upside-down with Eve Arden? (At least he'd get one laugh) why is he hanging upside-down with Eve Arden? So many questions....Glenn Mitchell does the commentary for A Day At the Races and it's pleasant for me, as an Englishman, to listen to his restful tones as he expounds on many fascinating points from this flawed, overlong, troubled yet ultimately very funny movie. The commentary on A Night At the Opera is by Leonard "One of the Team's Best" Maltin, and again it's a model of entertaining and informative.... whoaaa! Just a minute there, boy! I really hate to do this, Lenny old son, but it's all in the cause of accuracy.

Maltin says that the Father of All Marxes, Sam "Frenchie" Marx, is an extra in the dockside scene of A Night At the Opera, apparently causing a continuity error by appearing on the ship and the dock in consecutive shots. I hate to say this, Len old chap, but there's no way Sam could appear in A Night At the Opera except in a box. He died on May 11, 1933 and thus missed this particular boat by more than two years.

The good news is: he's in Monkey Business. This time the Marxes, as stowaways, are trying to get off the boat. Sam appears at about 48:01 into the movie and he's clearly visible until 48:22 (based on the DVD timing which includes the new Universal logo at the beginning) as the brothers are taken off the ship on a big stretcher. Initially he's seen in a long shot, waving his handkerchief, then in a medium shot sitting on (apparently) a trunk with a couple of young women. He looks very dapper: white hat, dark jacket, white pants and two-tone shoes. He resembles an off-duty Harpo. A freeze-frame at about 48:20 will give you a lovely shot of all four Marx Brothers and their Dad. A priceless moment.

The good news is: he's in Monkey Business. This time the Marxes, as stowaways, are trying to get off the boat. Sam appears at about 48:01 into the movie and he's clearly visible until 48:22 (based on the DVD timing which includes the new Universal logo at the beginning) as the brothers are taken off the ship on a big stretcher. Initially he's seen in a long shot, waving his handkerchief, then in a medium shot sitting on (apparently) a trunk with a couple of young women. He looks very dapper: white hat, dark jacket, white pants and two-tone shoes. He resembles an off-duty Harpo. A freeze-frame at about 48:20 will give you a lovely shot of all four Marx Brothers and their Dad. A priceless moment.Leonard Maltin probably realizes his mistake by now and he's kicking himself. Why didn't he ask Glenn Mitchell? It's all in The Marx Brothers Encyclopaedia.

Amongst the special features on the Marx Collection DVD set is a terminally useless MGM two-reeler, Sunday Night At the Trocadero, which has the benefit of idiotic and pointlessly brief guest appearances by a number of movie people who happened to be nearby at the time. Its relevance to this collection is the sight of a non-mustached Groucho on a rare night out with his wife Ruth (although the whole thing looks as if it was shot in the studio); all of which brings us back to Monkey Business. As Groucho performs his Chevalier impression we can see, in the background, a young woman and two boys. I suggest that this is Ruth Marx and that one of the boys is their son Arthur, no doubt dreaming of that time in the far future when he would work with some of the greatest comedians in America and vilify them in sloppily-researched biographies. Has this been suggested before? Ruth certainly visited the set of Animal Crackers; she was photographed with Groucho at the Art Deco table used in the Groucho-Chico "left-handed moths ate the painting" routine. Come on, Third Banana readers: let's argue!

After all this, I hear you saying: "you've written all this stuff - who's the Third Banana?"

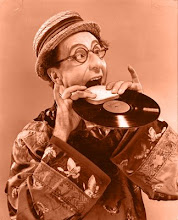

Well, it's Chico. He's always been regarded as the least important Marx (has everyone forgotten Zeppo?) yet his wily not-as-stupid-as-he-appears fake Italian frequently matches Groucho in timing and verbal dexterity; and he can out-scam anyone, especially Groucho. Often considered as just a straightman for his zanier siblings, of course he's much more than this, providing a bedrock of audience sympathy because we all recognize and love this cheeky con-artist. Despite his obvious phoniness he's nonetheless the most real, and the most lovable, and it's all done with the minimum of effort; an "Italian" Sid James. Hancock and Kenneth Williams were jealous of Sid; Groucho was jealous of Chico. It all has to do with charm, sex appeal and charisma. Chico must never be underestimated or overlooked, as he so often is. He was to the Marxes what Secombe was to the Goons.

Well, it's Chico. He's always been regarded as the least important Marx (has everyone forgotten Zeppo?) yet his wily not-as-stupid-as-he-appears fake Italian frequently matches Groucho in timing and verbal dexterity; and he can out-scam anyone, especially Groucho. Often considered as just a straightman for his zanier siblings, of course he's much more than this, providing a bedrock of audience sympathy because we all recognize and love this cheeky con-artist. Despite his obvious phoniness he's nonetheless the most real, and the most lovable, and it's all done with the minimum of effort; an "Italian" Sid James. Hancock and Kenneth Williams were jealous of Sid; Groucho was jealous of Chico. It all has to do with charm, sex appeal and charisma. Chico must never be underestimated or overlooked, as he so often is. He was to the Marxes what Secombe was to the Goons.Atsa some joke, eh, boss?

Well, that's about enough of that. Time for another look at A Night At the Movies. Benchley's brilliant but (surprise surprise) I won't be watching him. Goodnight everybody. Who is that lovely woman - and where's my time machine?

Labels: cinema, The Marx Brothers